Birds do it. Bees do it. And these days, with an unprecedented 100 million people on the move, more humans are doing it than at any time in recorded history. In response, states around the world have shut their doors and battened down the hatches.

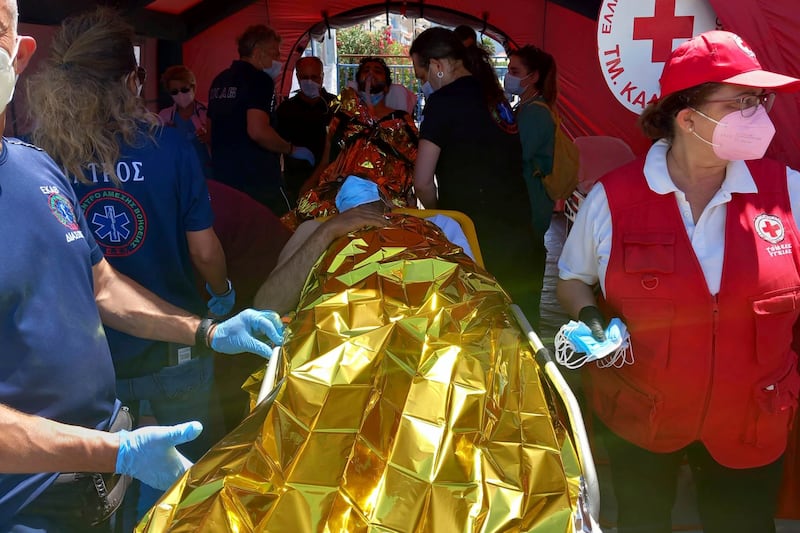

The tragic sinking of the Adriana off the Greek coast earlier this month was probably the deadliest migrant disaster in recent history, with as many as 600 people – from Pakistan and Egypt, Syria, the Palestinian territories and beyond – perishing in the Eastern Mediterranean.

That it happened despite activist groups and Greek and European authorities monitoring the creaky, Libya-launched vessel for the previous 15 hours makes the disaster all the more heart-rending for being wholly avoidable. When European leaders meet at this week’s EU summit in Brussels, one hopes they appreciate their role in this chronicle of a catastrophe foretold.

About eight years ago, western and European sympathies were largely with migrants. We were horrified by the 2013 shipwreck off Lampedusa that killed more than 300, then heartbroken at the sight, in the summer of 2015, of little Alan Kurdi washed up on a Turkish beach.

Down went the gates and in rushed up to two million Syrians, Iraqis, Afghans, Iranians, Africans and South Asians. Germany alone welcomed a million new arrivals. But European politics soon turned nativist after a few deadly terror attacks and hoary far-right warnings of a coming “Eurabia”, and even some of the continent’s liberal-minded leaders began to see the danger of too many new arrivals.

The first shoe fell in early 2016, when the EU agreed to pay Turkey €6 billion ($6.5 billion) to curb smuggling, accept the EU’s rejected asylum-seekers and indefinitely host some four million refugees. With this green light, Europe hardened its policies – beefing up border security agency Frontex and downgrading migrant search and rescue operations. Italy approved a controversial decree imposing stricter conditions on NGOs rescuing migrants, while Greece was charged with turning around migrant-laden boats at sea and pushing them back towards Turkey.

In late 2019, European parliament rejected – by two votes – a plan to significantly expand search and rescue operations for migrants in the Mediterranean, and the die was cast. The next year, after Turkey encouraged refugees to head for the Greek border and Athens mounted a stiff response, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen hailed Greece as Europe’s immigration shield.

In mid-2021, as such thinking gained ground, I warned of more Alan Kurdis to come. Six months later Russian forces invaded Ukraine, ultimately driving about 10 million Ukrainians into Europe. Now here we are, with migration, and migrant deaths, making a major resurgence.

From 2020 to 2022, the number of people arriving in Britain by boat increased five-fold, from 8,500 to more than 45,000, according to UK government figures. The US has repeatedly set new records for new arrivals at its Mexico border. Cypriot authorities last week rescued more than 80 migrants off the island’s south-east coast, and officials say boat arrivals are up 60 per cent this year.

The German news website Qantara reported that nearly 54,000 migrants have arrived in Italy this year as of mid-June, already twice as many as all of 2022, while the number of migrants killed while headed to Italy is up more than 30 per cent. Overall, more than 25,000 migrants have died attempting to cross the Mediterranean since 2014, according to German firm Statista.

All this helps explain why the EU-Turkey deal has begun to emerge as a model, despite leaving tens of thousands of migrants in limbo in overcrowded Greek camps. The EU has offered Tunisia a €900 million “partnership programme” that provides budget assistance and would ensure Tunis’s full co-operation on migration, including stronger border management and anti-smuggling efforts. The deal was to be finalised on Tuesday.

The EU has given Egypt about $100 million in the past few years to bolster its border security and anti-smuggling efforts, and just last week EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell pledged about $20 million more for Cairo, citing the outbreak of war in neighbouring Sudan.

European anti-migration funds are reaching even deeper into Africa. Last year, Rwanda and the UK signed a deal under which illegal arrivals to the UK would be flown to Rwanda, where they would be granted asylum and given settlement funds.

British refugee groups have challenged the plan and are awaiting a court decision, but the momentum seems clear: Fortress Europe is largely unconcerned about what happens beyond its parapets, as seen in the convincing re-election of a strongly anti-migrant government in Greece on Sunday.

The number of migrant deaths could soar, but as long as the number of new arrivals is kept to a minimum, the EU will continue to shell out good money, sacrificing its morality for a sense of political and social security while forcing emigrants to find new pathways.

On a class trip to Italy earlier this month as part of the Erasmus programme, an 11th-year student from a Turkish high school excused himself from a group meeting to visit the bathroom. An hour later, as teachers started wondering where he had gone off to, a text message arrived. “Don’t call me,” the student advised. “I won’t come back.”

He was already on a train headed for Germany, where he would check into a refugee camp and apply for asylum. As Turkey’s economy has drifted into rough seas over the past few years, the country’s youth have made for the EU in droves. The number of under-18 Turks seeking asylum in Germany has leapt six-fold in two years, according to Turkish journalist Elmas Topcu, and this Erasmus route is increasingly popular.

It’s far from the only novel path. Somalis have taken to obtaining health-related visas for Turkey only to make their way to a boat bound for Greece. Desperate Central Americans have hidden in airplane landing gear to reach the US and countless Syrians have flown to Belarus to wander blindly through dense forest in the hopes of stumbling into the EU.

There are surely other routes of which we are unaware, and refugees will in the months and years to come find new entryways, just as western powers will hit on new means to block their way. We are failing the world’s neediest, and every day we sail deeper into dark, stormy seas. Here’s hoping it’s not too late for a course correction.